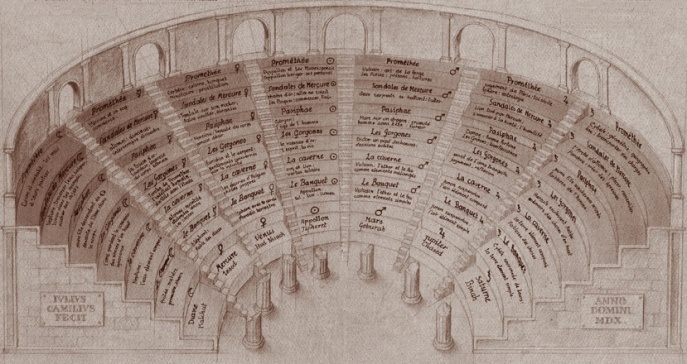

- Since I am at Ashland’s Oregon Shakespeare Festival, I am thinking about what the scholar Frances Yates (in Theatre of the World) argued was the inspiration for the Globe theater, Giulio Camillo’s plan for a metaphysical theater. It was to combine all knowledge, thereby acting as a kind of supercomputer and bringing about spiritual Enlightenment in the audience. It was a meme that swept through the late Renaissance and is suspected to be behind much of the great literature of the time from Shakespeare’s all-the-world’s-a-stage trope to Cervantes Don Quixote (see “El Quijote y El teatro de la memoria de Giulio Camillo”). Among other things, Camillo’s plan was a memory-training device. If you wanted to memorize something, you could imagine parts of it on associated places on Camillo’s stage, which had 49 sections, with labels of planets, Kabbalistic stages of development from God to the world, etc.

- Such a memory device had been common since classical antiquity and has been supported by the latest brain research. A 2002 British study used MRI to see how the best memorizers worked and found that they activated simultaneously the mnemonic and place locator cerebral areas. This was confirming the already compendious clinical evidence NLP has generated. It trains people’s memories with such imaged locations. Indeed, people tend to have an imagined spatial arrangement of their memories (e.g., with the past further away if that is how they feel about it). For many people, the arrangement is a line. How that line is oriented to the person’s body (e.g., running in front of it or through it) has significant implications for the person’s attitude toward time and many other things. Achieving high-numbered Graves/Jung Levels, however, often comes with a rearrangement of time positions from the simple line to a more complex temporal-spatial image, such as Camillo’s stage (or its latest version, the computer).

- How did he arrange memories? His axis of 7 planets (associated with personality) and 7 Kabbalistic archetypes of universal evolution was an attempt to indicate a 7-part pattern of universal development, but, alas, he was very vague, perhaps, as has been suggested by one scholar, to hide his support for various notions heretical at that time such as that the earth moved.

- At any rate, Camillo’s description of what vision his theater was to impart is the kind of mysticism common among those who take the Unconscious seriously, e.g., an animistic, holographic universe, where spiral energy patterns control some sort of seven-part emergence scheme.

- Did he intend anything like the Graves/Jung schema? Who knows? But at least according to Yates, it inspired those who, like Shakespeare, saw art (and in particular the stage) as a means to guide mankind as it developed through its so-called “Seven Ages” (for which see As You Like It 2.7)

Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s Auteur Theme

Standard

In 2001, I saw King Lear at London’s reproduction of the Globe. Its souvenir shop had a series of books on occult lore in Shakespeare’s works. None, though, were about The Tempest nor Midsummer Night’s Dream, the plays most connected to magic. Since then, I’ve been looking. The closest I’d found was Ted Hughes’ Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, which touches on Shakespeare’s knowledge of Hermetic magic, but excludes Midsummer Night’s Dream, because Hughes thought it contradicted his theory of Shakespeare’s advocating feminine power. Today, I encountered Katherine Bartol Perrault’s dissertation: “ASTRONOMY, ALCHEMY, AND ARCHETYPES: AN INTEGRATED VIEW OF SHAKESPEARE’S A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM.”

In 2001, I saw King Lear at London’s reproduction of the Globe. Its souvenir shop had a series of books on occult lore in Shakespeare’s works. None, though, were about The Tempest nor Midsummer Night’s Dream, the plays most connected to magic. Since then, I’ve been looking. The closest I’d found was Ted Hughes’ Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, which touches on Shakespeare’s knowledge of Hermetic magic, but excludes Midsummer Night’s Dream, because Hughes thought it contradicted his theory of Shakespeare’s advocating feminine power. Today, I encountered Katherine Bartol Perrault’s dissertation: “ASTRONOMY, ALCHEMY, AND ARCHETYPES: AN INTEGRATED VIEW OF SHAKESPEARE’S A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM.”

She dwells on the play’s repeated use of the number 4, e.g., four groups of characters, 4 days’ action, symbolism of 4 elements. Then she launches into astrology–not just the pervasive moon references–but the summer constellations reflected on the stage, with the right side the constellation Ophiucus/Asclepius (masculine–associated with Theseus/Oberon); stage left Virgo (feminine–associated with Hippolyta/Titania); and up stage Draco (dragon’s cave/womb), the alchemical/sexual vessel of transformation in Titania’s bower.

In the complete works of Shakespeare, there is considerable evidence that he was at least sometimes interested in alchemy, astrology, and magic. Like Hughes, though, I would like these to add up to more than male chauvinism: Theseus wins his wife by conquering her; Oberon tricks his into giving him a kidnapped boy by intoxicating her with a drug that causes her to sleep with aa donkey-headed oaf. For Perrault, this is fine because she assumes Shakespeare was that patriarchal and essentialist, thinking the boy better off if raised by the male. Furthermore, Oberon is not really asking to have the boy away from her, since he says that if she gives him the boy, he will go with her, which is to say that she will have access to the boy. Their argument, which interferes with the weather, comes from her wanting the boy away from him, causing her to withdraw from his bed.

What I suspect, is that Shakespeare was not writing occult allegory about stereotypical opposites brought into alchemical conjunction, but subverting traditional patterns in a complex way. After all, patriarchal rights per se are embodied in Hermia’s father, whom Shakespeare sets up for a fall. Furthermore, as Perrault admits, Hermia’s name is a form of the phallic male, Hermes, whereas Demetrius’ name comes from the Great Mother, Demeter–a constant undercuttng of gender stereotypes throughout the play.

Like Prospero in The Tempest or Hamlet in Hamlet or Portia in The Merchant of Venice, Midsummer Night’s Dream has at its core, a dramatist-like inventor of action (Oberon), a surrogate for Shakespeare’s own role in his troop. As such, Oberon’s desired objective would be the boy as an audience, someone to attend to him. Power goes to the most flexible and creative: Theseus who lets his heart be conquered by the one he conquered and more so Oberon, who manipulates a way to join all four couples happily, thereby restoring the weather. The play is about the victory of creativity, even the ignorant creativity of the craftsmen players, who succeed despite their ineptitude; but the fairies are the most powerful because they are the closest to the Unconscious, the psychological dynamo behind the magic. Where I appreciate Perrault’s interpretation is her recognizing that the many negative references to “moon” and “month” relate to the virgin goddess Diana, namesake of Titania and deity of Hippolyta. I see that virginity as the opposite of creativity and thus the reason that Theseus and Oberon win against the votaries of the moon.

Healing Narratives: An Introduction

StandardI was in the midst of writing this post inspired by a post on the WisconZen blog: “There is no “me”, but the story I tell myself.” I was thinking of all the healing narratives I know such as stories about healing by the founder of Hassidism, the Baal Shem Tov, which are themselves expected to generate further healings when they are retold. Then the phone rang and my wife informed me about the documentary “Shakespeare Lost, Shakespeare Found,” on Oregon Public Broadcasting.

It is about a computer re-creation of a previously lost play partly by Shakespeare, “The History of Cardenio.” You can see a trailer for it at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c5YT_c-pLXc. Naturally, I thought, ah hah!, if we are ourselves only stories then the way to heal is to heal the stories, what this computer recreation was doing.

So I looked a little further and found that in the 21st century two completely different plays have been staged as the lost “History of Cardenio,” a comedy (the one put forward by the documentary)

and a bloody tragedy.

This is not an old episode of “What’s My Line,” where we ask at the end for the real Cardenio to stand, because neither claims to be precisely the original, the first in particular having gone through highly speculative reconstruction, more post-human prosthetics than traditional medicine.

I am thus very grateful to my wife for pointing me in this direction, because if a theory of healing narratives were easy, we would all be well already. Furthermore, the story of Cardenio, originally in Cervantes Don Quixote, itself is about the problematics of healing narratives. As much clinical evidence now suggests likely as the chief healing use of narratives, the character Cardenio is being brought out of madness by being allowed to tell his tale. When, though, Don Quixote, who has his own mental problems, interrupts. Cardenio’s psychosis again manifests. Only being allowed to continue later returns him to reasonableness.

But the matter is more complicated. What drove Cardenio insane was treachery by a presumed friend, whom Cardenio had himself driven insane with a story. So narratives are what the Ancient Greeks called a pharmakon, medicine or poison depending on the context. We thus have puzzles I shall try to solve with subsequent postings in this series.